As Black professionals with degrees and decades of experience in counseling, we continue to be flabbergasted, dismayed, and upset about the persistent and pervasive under-representation of Black and other minoritized professionals in counseling, psychological, and mental health professions. Whether one is a preschool, elementary school, high school, or college student of color, there is an abysmally low probability that they will have a counseling provider in a school, agency, or hospital – from their racial and ethnic background. This is especially the case for Black males. Dr. Donna Y. Ford

Dr. Donna Y. Ford

Whether white or minoritized, we are very concerned about the delivery of services with and without a multicultural focus and/or experiences, as well as troubled about providers’ level of comfort, knowledge, skills, and experiences working with Blacks and other clients of color. Broadly speaking, the counseling profession comprises mostly white helping professionals in which many are insufficiently equipped and trained in multicultural, cross-cultural, or transcultural counseling. With an increasingly growing diverse society, it is critical that service providers hire counselors, who are anti-racist and culturally competent that reflect the population that being service. The same holds true with the goals and objectives of professional development workshops.

Multicultural, cross-cultural, or transcultural competency undergirded by an anti-racist philosophy is needed among all professionals, including counseling. When counselors are cultureblind (Ford’s substitution for “colorblindness”), they are frequently uncomfortable, unable, and/or unwilling to address their clients’ prejudices (i.e., individual, institutional, structural, systemic) or racist beliefs. It is well noted that clients of color benefit from racial/ethnic matching, meaning that counselors are likely to share some or much of the lived experiences of the same-race/ethnicity clients. In our experiences, when counselors have high levels of cultural awareness and pride, they are likely to express and promote racial and ethnic pride, affirm their clients’ experiences, share coping and empowering strategies and resources, and otherwise serve as cultural brokers/bridges. Dr. James L. Moore, III

Dr. James L. Moore, III

Not surprising to us, as discussed by Kafka, for decades, a growing number of students with psychiatric and neurodiverse histories, conditions, and medications have been enrolling in college. From an access standpoint, this is terrific. Thus, from a counseling standpoint, it has meant a professional state of siege. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing and increased racial and ethnic prejudice and discrimination, counseling providers, particularly for Asian and Black clients, are struggling to keep up with requests for help and guidance wreaked on students of color. Data on students’ mental health from the Healthy Minds Network have shown increasing anxiety and depression over the past 10 years. Data from the network’s spring survey revealed a rise from the fall of 2020 to the spring of 2021 in students who screen positive for anxiety (which grew from 31% to 34%) and depression (which increased from 36% to 41%).

A poignant reminder by Kafka is that some colleges’ counseling centers are creating more counseling and support groups to help meet the demand, but it is also in response to the needs of racial-minority (or LGBTQ) communities, students who share a particular diagnosis, students who might benefit from a specific type of therapy, or students who have common goals or problems. We added the italics to the assertion regarding ‘needs’ to highlight/emphasize that counseling must be client-centered as we and others promote and admonish in education and counseling fields. The need to recruit and retain counselors does not do justice to the work that must be done when white and minoritized counselors are not culturally competent. Our grave concerns pertain to counselors adopting cultureblindness on the one hand to being culturally assaultive on the other hand.

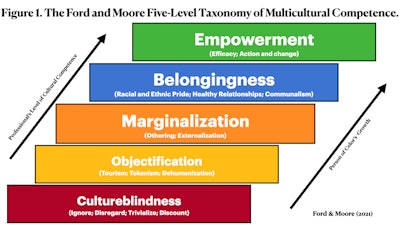

Considering the above, it is no wonder that, per Kafka, more students are seeking help and their suffering is more acute. There is a need more counselors but finding them is challenging. Efforts by several colleges to meet the demands are described by Kafka; however, worth emphasizing is the need for counselors is more pressing and urgent for those of color and those individuals who are anti-racist and culturally competent. Being ever mindful that representation and cultural competence are crucial, we introduce our taxonomy or levels of multicultural content into counseling. This model is grounded in the work of James A. Banks’ four approaches of infusing multicultural content into the curriculum. In our five-level, cultural competence model, the focus is on the content of counseling sessions – goals, topics, issues/problems, materials and resources, and strategies.

For approximately two decades, we have collaborated in the spirit and advocacy for Blacks and other individuals of color to support them in gaining access to professionals who are anti-racist and culturally competent and/or who share their race and ethnicity with cultural pride. This includes, but is not limited to, students, families, educators, counselors, administrators, and faculty. Figure 1 depicts our Five-Level Taxonomy of Multicultural Competence. We apply it below to school counselors, but it can be adopted for other disciplines (e.g., education, curriculum developers, etc.). Keywords for each level are listed. For the professional, the arrow indicates level or degree of cultural competence. For clients (or students, etc.), the arrow shows the idea and ideal of change and progress in meeting goals and objectives – growth. It also represents feelings and reactions to counseling and the counselor at each level. We explain this more in forthcoming publications.

At the lowest level is cultureblindness. Counselors are not aware of cultural differences (i.e., assets) or are aware of culture, but deny that it matters by ignoring, discounting, and trivializing the culture of clients. No effort is made to discuss racialized experiences, both positive or negative, and no responsibility is given to their being racist and culturally assaultive in words and actions (e.g., behaviors, expectations, materials, techniques, and goals) toward clients. Too often, people color and other diverse populations feel invisible, frustrated, resentful, and angry due to implicit and explicit biases. When Black clients, in particular, feel rejection and alienation from the counselor, they often request another counselor and, when not available, they often terminate the counseling experience and may not seek help again.

The next level is objectification, whereby counselors equate clients of color with what we and others call the Four Fs – Food, Fun, Fashion, and Folklore. The counselor is aware of culture in a superficial, stereotypical, and tourist manner. Stereotypes guide their work. Minoritize clients feel that their individual and racial/ethnic group identity is dehumanized, relegated to objects rather than ideas, experiences, and ways of being. Although some people of color feel seen, many are still perceived in negative, humiliating, deficit-based ways. Such feels often contribute to anger or rage and frustration, along with alienation and disconnected from the counselor. If possible, they request another counselor. When not available, they terminate the counseling experience and are reluctant to pursuing counseling assistance or help again.

Marginalization is the third approach or level of our taxonomy. It is not uncommon in schools and non-school contexts that Blacks and other people of color feel devalued and marginalized in American society; they feel unwelcome, as outsiders. The client-counselor relationship is strained because a relationship has not been developed or initiated by the counselor (e.g., getting to know about client’s background, interests, goals, lived experiences, etc.). When talking about racial and ethnic prejudice and discrimination, counselors are dismissive and may resort to placing the onus of clients’ racialized issues and problems, resorting to blaming the victim. Helplessness, frustration, anger, indignation, and/or defensiveness ensue on the part of many Black clients and counseling consumers of color.

The fourth approach or level is Belongingness, which we align with racial and ethnic pride. Such an identity centers squarely on race-based self-perception, self-concept, self-esteem, and group affiliation. Counselors are culturally competent in knowledge, skills, and dispositions, based upon educational and multicultural experiences. This includes their ability to empathize with and have compassion for culturally different clients. They are keenly aware that both prejudice and racism exist, and they take a toll on people of color (e.g., racial battle fatigue, internalized racism, disdain for whites, etc.). Time is devoted to building positive and culturally affirming relationships with clients, along with session on minoritized clients’ racial or ethnic identity development and needs. They have an asset-based philosophy regarding culture and associated similarities and differences. When counselors feel confused and/or ineffective, they seek guidance from colleagues of color and/or whites who are considered culturally competent and anti-racist. To this end, such counselors commonly utilize rigorous and relevant resources, materials, theories, research, and techniques grounded in culture to promote and nurture racial and ethnic identity.

To connect with their clients, culturally competent counselors are conscious of the effects racial and ethnic variables, viewing this culturally-based psychological construct as a source of strength (similar to socio-emotional development, self-concept, and self-esteem). They set mutually agreed upon goals and objectives with Black clients and other of color. Positively, minoritized clients feel seen in affirmative ways. They feel cared about and a valued member of this professional relationship. They are comfortable discussing racialized encounters (e.g., microaggressions) with counselors from all racial and ethnic groups, and appreciate that their culture is being used with academic, social, affective, psychological, vocational, and personal concerns, issues, and problems so that the experience is productive – goals and objectives are met. Clients of color would be aware and understanding of Cross and Vandiver’s internalization stage or phase of racial identity development and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs’ self-actualization level.

Empowerment is the highest level and the most culturally responsive approach in which Black and other clients of color, armed with belongingness, are proactive about addressing problems and concerns for themselves, and perhaps those of others in their racial and ethnic group and communities. They feel efficacious about their ability to cope with and resolve challenges that, prior to counseling, seemed insurmountable. Counselors have been instrumental in providing cathartic experiences by having someone to talk to who listens to understand and support with resources (e.g., literature, theories, research, same-race role models and mentors, opportunities, etc.). Such transculturally competent counselors have the knowledge, dispositions, experiences, and skills to be an advocate or ally to their minoritized clients. They adhere to the multicultural competencies developed by the Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development in 1991.

Recommendations, Summary, and Conclusions

The counseling profession cannot wait for the field to become more diverse. It must simultaneously diversify the profession and train counselors to be anti-racist and culturally competent. Presenters must include people of color. Below are some of the topics that we recommend that the counseling profession devote considerable commitment and time:

1. Higher education formal training must have anti-racist, culturally courses, endorsements, licensure, and degrees. Field experiences need to be in diverse communities. Projects and assignments must be focused on minorized individuals and groups with the goal of immersing counselors in the communities of their clients. Counselors should not graduate only to find that they are ill-prepared to work with real clients with real culturally-based academic, social, affective, and psychological issues and needs.

2. Professional development in the workplace must also focus directly on supporting school counselors. Sample topics here and in other organizations and settings should include theories, research, along with prevention and intervention strategies, models, and programs grounded in the culture(s)of each racial and ethnic group. Homogenization must be avoided. Efforts must support counselors in their ongoing development to be effective and culturally responsive and competent.

3. Professional development in mainstream and multicultural professional organizations provide important outlets for counselors to have increased contact and interactions with culturally different individuals. Real world experiences increase multicultural efficacy.

4. Recruitment of minoritized counselors is essential, as previously stated. They serve as cultural brokers to clients of color and as resources to white counselors.

Dr. Donna Y. Ford is a Distinguished Professor of Education Human Ecology at The Ohio State University. Dr. James L. Moore III, is a Distinguished Professor of Education and Human Ecology and Vice Provost of Diversity and Inclusion and Chief Diversity Officer at The Ohio State University.